Community-in-the-loop: accountability must drive AI development in humanitarian response

By Helen McElhinney, Executive Director of CDAC Network

For more than 15 years, the CDAC Network has worked with humanitarian and media development actors to strengthen communication with communities, accountability to affected populations, and collective approaches to trust in crisis response. Across conflicts, disasters, and protracted emergencies, one lesson has remained consistent: humanitarian action works best when people affected by crises are informed, listened to, and able to question the system that serves them.

These values and commitments are now being tested with the rush to utilise AI.

Artificial intelligence is already shaping humanitarian decision-making — from analysis and anticipation to information provision, targeting, and verification. Needs are rising, and expectations of efficiency are growing.

In some cases, AI offers a real opportunity. In others, it introduces new risks of exclusion, opacity, and harm. The question is no longer whether AI will be used in humanitarian response, but rather how. As a sector, we need to make sure it is utilised in ways that uphold humanitarian values and trust, and that communities affected by crisis will have a meaningful say in how it works and impacts their lives.

At CDAC, we believe there needs to be a fundamental shift and commitment to accountability in AI, and we must centre the participation of communities affected by crises in tech innovation.

From human-in-the-loop to community-in-the-loop

We often hear about keeping the ‘human-in-the-loop’ with AI, which is the idea that a human should actively participate in the operation, decision-making or supervision of an AI process. This is an approach humanitarians should embrace, yet should take it one step further.

CDAC calls for a community-in-the-loop approach, which ensures people affected by crisis are involved in the design, deployment, and oversight of AI systems that impact their lives. It goes beyond including a human-in-the-loop – which could simply be a technical advisor at headquarters – and shifts power back to the communities.

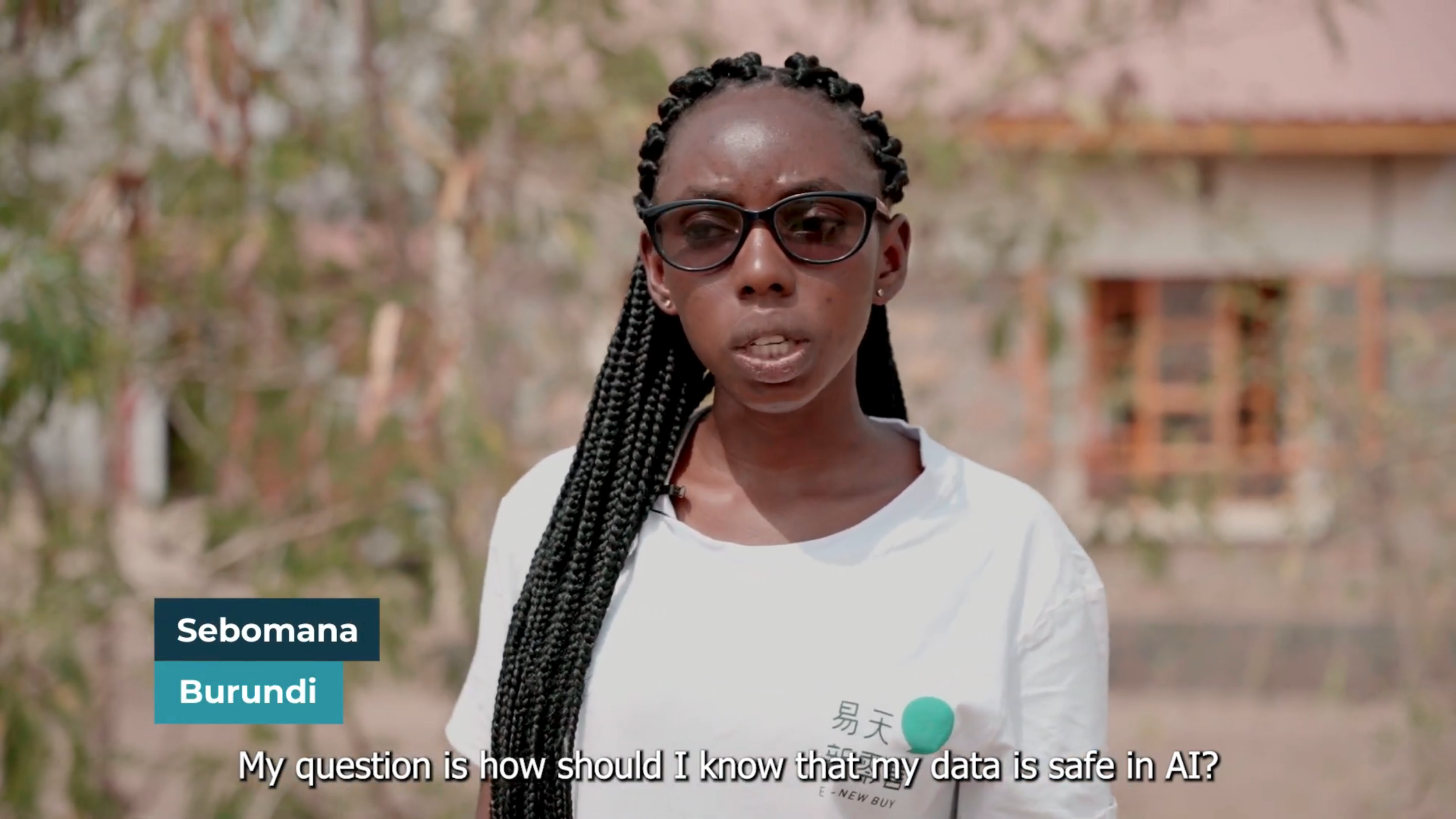

As Taiwan’s digital minister Audrey Tang has argued, the purpose of digital technology is not to make systems more powerful, but to make people less powerless. In humanitarian contexts, that distinction matters. Communities affected by crises must have genuine pathways to understand, question, and seek redress when AI-enabled systems influence the assistance they receive, the information they trust, or the decisions made about them. Such AI literacy is not a luxury but an urgent prerequisite for accountability, participation, and trust when automated systems shape people’s lives.

This is why CDAC Network, The Alan Turing Institute, and Humanitarian AI Advisory have been developing the SAFE AI Framework: tools and guidance to help humanitarian actors, donors, and communities planning or using AI to apply safeguards proportionate to context and risk.

The SAFE AI project reflects CDAC Network’s long-standing conviction that accountability, participation, and protection must extend to the information systems humanitarian actors rely on — including those powered by AI. In an environment where information can determine access to aid, exposure to harm, or trust in institutions, treating the health of the information environment separately from aid is no longer optional.

Crucially, SAFE AI’s foundations were shaped by early guidance from refugees in Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya. Their reflections on trust, accountability, and who bears the consequences when systems fail challenged assumptions about neutrality and risk-sharing, grounding the work in lived realities too often absent from technology debates. This input reinforced a core insight: innovation must be shaped with those most affected by its use, not only by headquarters or donors.

From participation to transparency and ‘the right to know’

Meaningful community-in-the-loop governance also requires clarity about when and how AI systems are used. A growing norm in global AI governance discussions is a ‘right to know’ — that individuals should be informed when they are interacting with an AI system, or when AI materially influences decisions that affect them.

In humanitarian contexts, this is essential. Where automated systems shape eligibility, targeting or verification, transparency must be embedded into design. Disclosure, accessible explanation and clear pathways for human review are not optional features — they are the safeguards that protect trust and uphold humanitarian principles.

Participation must therefore extend beyond consultation to include influence over architectural choices, guardrails and red lines — particularly in high-risk settings.

“Accountability infrastructure must try to move as fast as innovation. Where AI-enabled systems outpace people’s ability to question decisions or seek remedy, trust erodes quickly and is difficult to rebuild.”

Accountability before scale

If the humanitarian system is to retain trust — and importantly, the trust of people affected by crises — innovation must remain anchored in participation, accountability, and the ability to listen and respond when things go wrong.

One of the clearest lessons from CDAC’s work on collective accountability is that accountability infrastructure must try to move as fast as innovation. Where AI-enabled systems outpace people’s ability to question decisions or seek remedy, trust erodes quickly and is difficult to rebuild.

Audrey Tang’s experience in Taiwan shows that digital and AI-enabled systems can be designed to expand participation while strengthening accountability — but only where literacy, transparency, and redress are treated as governance requirements. For humanitarian leaders, this reinforces a simple point: AI use and accountability to people affected by crises are not trade-offs, but two sides of the same coin.

To make that opportunity real, the IASC-led system will need to revisit:

How data collected from communities is reused. In a period of severe funding constraints, re-analysing existing needs assessments or feedback data can appear both efficient and benign. But when combined with AI, this practice carries real trade-offs. Without careful design, it risks creating a false sense of participation, reinforcing outdated or incomplete views of communities, or substituting historical data for present-day dialogue.

Re-imagine informed consent alongside other participatory safeguards, as the participatory potential of AI should not depend on shortcuts. For example, ensuring that data re-use strengthens agency and trust, rather than quietly undermining them.

Who owns and benefits from humanitarian data. As Mariana Mazzucato has argued, data generated through public or collective activity should be treated as a source of public value, not simply a private asset to be extracted for profit. UN digital cooperation efforts similarly frame data governance as an issue of rights, accountability, and trust, not just efficiency.

Community-in-the-loop is one part of how we will get there. Putting communities and people at the centre of humanitarian response and making sure AI innovations are accountable by design, not as an afterthought.

The upcoming SAFE AI Framework is a practical toolkit deliberately designed for a humanitarian system operating under constraint. It does not assume unlimited resources, specialist capacity, or stable operating environments. Instead, it encourages actors to build on what remains of existing investments in accountability to affected populations, safeguarding, and collective coordination — including those supported by bilateral donors and pooled funds, many of which are under severe strain.

In a period of tightening budgets, creating parallel AI-specific mechanisms is neither realistic nor responsible. Alignment, reuse, and collective approaches are practical necessities.